Overview

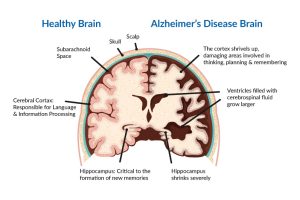

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurologic disorder that causes the brain to shrink (atrophy) and brain cells to die. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia — a continuous decline in thinking, behavioral and social skills that affects a person’s ability to function independently.

Approximately 5.8 million people in the United States age 65 and older live with Alzheimer’s disease. Of those, 80% are 75 years old and older. Out of the approximately 50 million people worldwide with dementia, between 60% and 70% are estimated to have Alzheimer’s disease.

The early signs of the disease include forgetting recent events or conversations. As the disease progresses, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will develop severe memory impairment and lose the ability to carry out everyday tasks.

Medications may temporarily improve or slow progression of symptoms. These treatments can sometimes help people with Alzheimer’s disease maximize function and maintain independence for a time. Different programs and services can help support people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers.

There is no treatment that cures Alzheimer’s disease or alters the disease process in the brain. In advanced stages of the disease, complications from severe loss of brain function — such as dehydration, malnutrition or infection — result in death.

Symptoms

Memory loss is the key symptom of Alzheimer’s disease. Early signs include difficulty remembering recent events or conversations. As the disease progresses, memory impairments worsen and other symptoms develop.

At first, a person with Alzheimer’s disease may be aware of having difficulty remembering things and organizing thoughts. A family member or friend may be more likely to notice how the symptoms worsen.

Brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease lead to growing trouble with:

Memory

Everyone has occasional memory lapses, but the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease persists and worsens, affecting the ability to function at work or at home.

People with Alzheimer’s may:

- Repeat statements and questions over and over

- Forget conversations, appointments or events, and not remember them later

- Routinely misplace possessions, often putting them in illogical locations

- Get lost in familiar places

- Eventually forget the names of family members and everyday objects

- Have trouble finding the right words to identify objects, express thoughts or take part in conversations

Thinking and reasoning

Alzheimer’s disease causes difficulty concentrating and thinking, especially about abstract concepts such as numbers.

Multitasking is especially difficult, and it may be challenging to manage finances, balance check books and pay bills on time. Eventually, a person with Alzheimer’s may be unable to recognise and deal with numbers.

Making judgements and decisions

Alzheimer’s causes a decline in the ability to make reasonable decisions and judgements in everyday situations. For example, a person may make poor or uncharacteristic choices in social interactions or wear clothes that are inappropriate for the weather. It may be more difficult to respond effectively to everyday problems, such as food burning on the stove or unexpected driving situations.

Planning and performing familiar tasks

Once-routine activities that require sequential steps, such as planning and cooking a meal or playing a favorite game, become a struggle as the disease progresses. Eventually, people with advanced Alzheimer’s often forget how to perform basic tasks such as dressing and bathing.

Changes in personality and behavior

Brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease can affect moods and behaviors. Problems may include the following:

- Depression

- Apathy

- Social withdrawal

- Mood swings

- Distrust in others

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Changes in sleeping habits

- Wandering

- Loss of inhibitions

- Delusions, such as believing something has been stolen

Preserved skills

Many important skills are preserved for longer periods even while symptoms worsen. Preserved skills may include reading or listening to books, telling stories and reminiscing, singing, listening to music, dancing, drawing, or doing crafts.

These skills may be preserved longer because they are controlled by parts of the brain affected later in the course of the disease.

Causes

The exact causes of Alzheimer’s disease aren’t fully understood. But at a basic level, brain proteins fail to function normally, which disrupts the work of brain cells (neurons) and triggers a series of toxic events. Neurons are damaged, lose connections to each other and eventually die.

Scientists believe that for most people, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors that affect the brain over time.

Less than 1% of the time, Alzheimer’s is caused by specific genetic changes that virtually guarantee a person will develop the disease. These rare occurrences usually result in disease onset in middle age.

The damage most often starts in the region of the brain that controls memory, but the process begins years before the first symptoms. The loss of neurons spreads in a somewhat predictable pattern to other regions of the brains. By the late stage of the disease, the brain has shrunk significantly.

Researchers trying to understand the cause of Alzheimer’s disease are focused on the role of two proteins:

- Plaques. Beta-amyloid is a fragment of a larger protein. When these fragments cluster together, they appear to have a toxic effect on neurons and to disrupt cell-to-cell communication. These clusters form larger deposits called amyloid plaques, which also include other cellular debris.

- Tangles. Tau proteins play a part in a neuron’s internal support and transport system to carry nutrients and other essential materials. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau proteins change shape and organize themselves into structures called neurofibrillary tangles. The tangles disrupt the transport system and are toxic to cells.

Risk factors

Age

Increasing age is the greatest known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s is not a part of normal aging, but as you grow older the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease increases.

One study, for example, found that annually there were four new diagnoses per 1,000 people ages 65 to 74, 32 new diagnoses per 1,000 people ages 75 to 84, and 76 new diagnoses per 1,000 people age 85 and older.

Family history and genetics

Your risk of developing Alzheimer’s is somewhat higher if a first-degree relative — your parent or sibling — has the disease. Most genetic mechanisms of Alzheimer’s among families remain largely unexplained, and the genetic factors are likely complex.

One better understood genetic factor is a form of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE). A variation of the gene, APOE e4, increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Approximately 25% to 30% of the population carries an APOE e4 allele, but not everyone with this variation of the gene develops the disease.

Scientists have identified rare changes (mutations) in three genes that virtually guarantee a person who inherits one of them will develop Alzheimer’s. But these mutations account for less than 1% of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Down syndrome

Many people with Down syndrome develop Alzheimer’s disease. This is likely related to having three copies of chromosome 21 — and subsequently three copies of the gene for the protein that leads to the creation of beta-amyloid. Signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s tend to appear 10 to 20 years earlier in people with Down syndrome than they do for the general population.

Sex

There appears to be little difference in risk between men and women, but, overall, there are more women with the disease because they generally live longer than men.

Mild cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a decline in memory or other thinking skills that is greater than normal for a person’s age, but the decline doesn’t prevent a person from functioning in social or work environments.

People who have MCI have a significant risk of developing dementia. When the primary MCI deficit is memory, the condition is more likely to progress to dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis of MCI encourages a greater focus on healthy lifestyle changes, developing strategies to make up for memory loss and scheduling regular doctor appointments to monitor symptoms.

Head trauma

People who’ve had a severe head trauma have a greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Several large studies found that in people age 50 years or older who had a traumatic brain injury (TBI), the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease increased. The risk increases in people with more-severe and multiple TBIs. Some studies indicate that the risk may be greatest within the first six months to two years after the TBI.

Air pollution

Studies in animals have indicated that air pollution particulates can speed degeneration of the nervous system. And human studies have found that air pollution exposure — particularly from traffic exhaust and burning wood — is associated with greater dementia risk.

Excessive alcohol consumption

Drinking large amounts of alcohol has long been known to cause brain changes. Several large studies and reviews found that alcohol use disorders were linked to an increased risk of dementia, particularly early-onset dementia.

Poor sleep patterns

Research has shown that poor sleep patterns, such as difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Lifestyle and heart health

Research has shown that the same risk factors associated with heart disease may also increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. These include:

- Lack of exercise

- Obesity

- Smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Poorly controlled type 2 diabetes

These factors can all be modified. Therefore, changing lifestyle habits can to some degree alter your risk. For example, regular exercise and a healthy low-fat diet rich in fruits and vegetables are associated with a decreased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Lifelong learning and social engagement

Studies have found an association between lifelong involvement in mentally and socially stimulating activities and a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Low education levels — less than a high school education — appear to be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

Complications

Memory and language loss, impaired judgement and other cognitive changes caused by Alzheimer’s can complicate treatment for other health conditions. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may not be able to:

- Communicate that he or she is experiencing pain

- Explain symptoms of another illness

- Follow a prescribed treatment plan

- Explain medication side effects

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses to its last stages, brain changes begin to affect physical functions, such as swallowing, balance, and bowel and bladder control. These effects can increase vulnerability to additional health problems such as:

- Inhaling food or liquid into the lungs (aspiration)

- Flu, pneumonia and other infections

- Falls

- Fractures

- Bedsores

- Malnutrition or dehydration

- Constipation or diarrhoea

- Dental problems such as mouth sores or tooth decay

Prevention

Alzheimer’s disease is not a preventable condition. However, a number of lifestyle risk factors for Alzheimer’s can be modified. Evidence suggests that changes in diet, exercise and habits — steps to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease — may also lower your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders that cause dementia. Heart-healthy lifestyle choices that may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s include the following:

- Exercising regularly

- Eating a diet of fresh produce, healthy oils and foods low in saturated fat such as a Mediterranean diet

- Following treatment guidelines to manage high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol

- Asking your doctor for help to quit smoking if you smoke

When to see a doctor

A number of conditions, including treatable conditions, can result in memory loss or other dementia symptoms. If you are concerned about your memory or other thinking skills, talk to your doctor for a thorough assessment and diagnosis.

If you are concerned about thinking skills you observe in a family member or friend, talk about your concerns and ask about going together to a doctor’s appointment.